After a first part where we have seen how to get move from vanilla JavaScript to React, let’s see how we can create real React components.

In order to introduce some dynamicity in our React code, we would like to execute functions to compute some JSX instead of relying only on static JSX code. We are lucky since React.createElement can take not only the name of a standard element (like div or h1) but also a function as a parameter:

const hello = () => 'Hello user';

const element = React.createElement(hello);

From what we have seen about JSX, it seems equivalent to this code:

const hello = () => 'Hello user';

const element = <hello/>;

Unfortunatly, this code would produce an error since it would be transformed to the following code instead:

const hello = () => 'Hello user';

// using the string 'hello' instead of the variable hello

const element = React.createElement('hello');

To make this work with JSX, we need to tell it how to differenciate between the name of a standard element that we want to create and the name of a function which will dynamically compute some elements. For that, there is a simple solution, the name of our function has to start with an uppercase.

const Hello = () => 'Hello user';

const element = <Hello />; // React.createElement(Hello);

With this, we can now define functions which will return complex trees of React elements quite easily. Please note that in order to use multiline JSX expressions, you will have to use parenthesis.

const Profile = () => (

<div>

<h1>Username</h1>

<p>Description of the user</p>

</div>

);

const element = <Profile/>;

This Profile function is our first React component. This component is just a simple stateless function which return some React elements defined using JSX. It is not very useful since it will always return the same elements. In order to create a more interesting component, we would need to compute the React elements using some input.

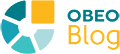

We can retrieve some properties in the first argument of our function. This argument is always named props by convention in the React community. In order to give some properties to a component, we will use regular JSX properties as we have seen in the previous article. Here is an example, in which we can specify the user that we want to consider using a property user.

const Profile = (props) => (

<div>

<h1>Username: {props.user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {props.user.description}</p>

</div>

);

const user = { username: 'Darth Vador', description: 'I am your father' };

const element = <Profile user={user}/>;

You can then render the React element produced in a similar fashion as in last week example. Don’t hesitate and try to create such component using CodeSandbox for example and see it rendered in real time.

While JSX may look like HTML, it is only a declarative language which will be converted to JavaScript. As a result, manipulating JSX will sometimes feel closer to JavaScript than HTML. For example, some DOM attributes will need to be manipulated thanks to their JavaScript name instead of their HTML ones.

Have a look at the React documentation to see the list of the attributes impacted. Most of the time, you just have to use the camel-case version of the HTML API but some attributes will have a different named like for which is htmlFor in JavaScript or class which becomes className.

When you will manipulate some JSX, keep in mind that in the end it’s just JavaScript. You can easily mix regular JavaScript expressions inside of some JSX code. For example, let’s consider this simple example:

const list = (

<ul>

<li>John</li>

<li>Jane</li>

</ul>

);

We could use a JavaScript expression to create both li elements from an array for example

const list = (

<ul>

{['John', 'Jane'].map(user => <li>{user}</li>)}

</ul>

);

We could also extract some behavior in another function to make our code more readable in complex use cases.

const createUser = (user) => <li>{user}</li>;

const list = (

<ul>

{['John', 'Jane'].map(createUser)}

</ul>

);

In the end, this code would be transformed in the following JavaScript code based on React.createElement

const createUser = user => React.createElement(

'li',

null,

user

);

const list = React.createElement(

'ul',

null,

['John', 'Jane'].map(createUser)

);

Of course, for such situation, we could transform our function into another component since createUser is expecting some data to create a React element. Let’s name it Item since it may be used for more than creating users.

const users = [{ "username": "John" }, { "username": "Jane" }];

const Item = (props) => <li>{props.entry}</li>;

const List = (

<ul>

{users.map(user => <Item entry={user.username}/>)}

</ul>

);

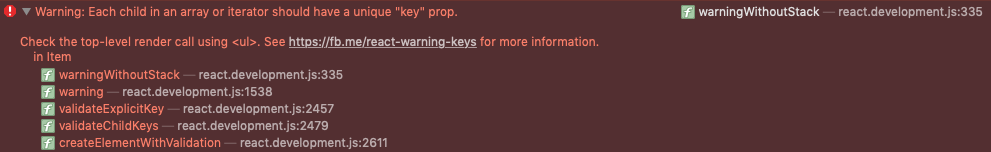

If you tried to execute those examples, you should have encountered the following error in your console, even if everything seems to work, we will see why a bit later.

The React components that we have created up until now have been very simple but a functional React component can leverage all the features of a regular JavaScript function to compute the React elements to return. As such, do not hesitate to use conditions, loops etc.

const HelloMessage = (props) => {

let hello = null;

if (props.user) {

hello = <div>Hello {props.user.username}</div>;

} else {

hello = <div>Hello stranger</div>;

}

return (

<div>{ hello }</div>

);

};

If you want to create a component which will not render anything in some situation, you just have to return null to prevent the rendering.

const HelloMessage = (props) => {

if (!props.user) {

return null;

}

return <div>Hello {props.user.username}</div>;

};

Some of our previous examples should have produced an error related to a missing key prop in the developer console. This error is caused by the fact that we are creating multiple elements of the same type at the same location in the DOM without giving React any indication to identify each element created.

React needs to be able to identify each element in order to refresh the user interface properly. React wouldn’t be able to find out precisely what has been changed otherwise. If you want to create a list of elements programmatically, you will need to give React a unique identifier for each element with a special property named key. The value of this property should be unique and robust over time.

Do not use something like the index of the value in the collection since it would create issue if you try to re-order or filter the collection. In the following example, we will use the username of each user as the value of the property key and now this error will disappear along with tons of potential refresh issues.

const users = [{ "username": "john" }, { "username": "jane" }];

const UserList = (props) => {

const users = props.users.map(user =>

<li key={ user.username }>

Username: { user.username }

</li>

);

return (

<ul>

{ users }

</ul>

);

};

ReactDOM.render(<UserList users={users} />, document.getElementById('app'));

As we have seen, you can define your React components as regular JavaScript functions but you could also use ECMAScript 2015 classes too. Using a class, the code of our functional component can be executed thanks to a method named render. In this method, we will retrieve the props object thanks to this.props since the method render does not have any parameter.

We could transform one of our previous example which was using a stateless functional component…

import React from 'react';

const Profile = (props) => (

<div>

<h1>Username: {props.user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {props.user.description}</p>

</div>

);

…into a class-based one very easily. Do not forget to use this.props instead of props and everything will be fine.

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class Profile extends Component {

render () {

return (

<div>

<h1>Username: {this.props.user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {this.props.user.description}</p>

</div>

);

}

}

This class-based component can be rendered by ReactDOM juste like a functional component.

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom';

class Profile extends Component {

render () {

return (

<div>

<h1>Username: {this.props.user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {this.props.user.description}</p>

</div>

);

}

}

const user = { username: 'Darth Vador', description: 'I am your father' };

ReactDOM.render(<Profile user={user}/>, document.getElementById('app'));

Class-based components are mostly used in order to create stateful components since they give access to additional methods to both maintain a state and update it to match the lifecycle of the application. We could perfectly create a stateless class-based component by not using anything related to state manipulation inside of the component. In fact, our previous example is a stateless class-based component but apart from some specific situations, it’s better to think about stateless components as functional ones and stateful components as class-based ones.

To create a stateful component, we will have to initialize its state in the constructor. The constructor will receive the props and it can use them to define the initial state. Once initialized, we can use the value of the state in the method render. We can use values from both props and state in method render, you don’t need to put everything from the props in the state once you write a stateful component. We will store in state the values that will be computed from the props and which will change over time thanks to interaction from a user or with a server for example.

We will react to user interactions with listeners on the React element and we will use lifecycle methods to trigger some calls to a server. In our case, the state will indicate if the component is currently loading and the user fetched from the server. For the first version of our component, we will not fetch anything from the server.

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class Profile extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

// Our initial state

this.state = {

isLoading: true,

user: undefined

};

}

render() {

const { isLoading, user } = this.state;

if (isLoading) {

return <div>Loading...</div>;

}

return (

<div>

<h1>Username: {user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {user.description}</p>

</div>

);

}

}

Now we will make sure that once our component is used, it will fetch the user from the server. For that we will use the lifecycle method componentDidMount() which is called once the component is mounted in the DOM. In this method, we will request the user from the server and then we will update the state of our component to re-render our element.

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class Profile extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

isLoading: true,

user: undefined

};

}

componentDidMount() {

fetch('https://domain.tld/api/users/me')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

this.setState({ isLoading: false, user: data });

});

}

render() {

const { isLoading, user } = this.state;

if (isLoading) {

return <div>Loading...</div>;

}

return (

<div>

<h1>Username: {user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {user.description}</p>

</div>

);

}

}

With this new version of our component, the component will first be instantiated, creating its initial state, and then displayed in the web page. For that the method render() will be called with our initial state and it will render our loading message.

Then the method componentDidMount() will be called and a request will be sent to the server. Once the response will be received, its JSON body will be parsed and we will use the method setState(...) to tell React to enqueue a state change which will trigger a new call to render. Keep in mind that the method setState(...) will trigger the re-rendering of the component asynchronously and, in some cases, multiple state changes can be executed in batch by React.

Once the state of the component has been updated, it will render its content again. This time, it will display the user information since our call to setState(...) will set isLoading to false. In our situation, our component will be rendered twice, once with the initial state and once when the response from the server will be processed.

We could also update the internal state of our component in reaction to some user interactions with the DOM. For that we could add a refresh button in our component which would fetch the data from the server manually. In order to listen to the click on the button, we will use a method which we will name handleClick.

We have to bind our method handleClick to the current instance, in the constructor, to prevent any issue during the execution, otherwise this would be null inside of handleClick which would prevent us from using this.setState(...).

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class Profile extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this);

this.state = {

isLoading: true,

user: undefined

};

}

fetchUser() {

fetch('https://domain.tld/api/users/me')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

this.setState({ isLoading: false, user: data });

});

}

componentDidMount() {

this.fetchUser();

}

handleClick() {

this.setState({ isLoading: true, user: undefined }, () => {

this.fetcherUser();

});

}

render() {

const { isLoading, user } = this.state;

if (isLoading) {

return <div>Loading...</div>;

}

return (

<div>

<h1>Username: {user.username}</h1>

<p>Bio: {user.description}</p>

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>Refresh</button>

</div>

);

}

}

We are also using the method setState(...) with a second parameter in order to give it a callback to evaluate once the state will be updated. When the user will click on the button, we will first change the value of isLoading back to true (which will re-render the loading message) and then fetch the user once again.

Today we have seen how to create our first React component and how to handle state inside of a component. Next week, we will have a closer look at the way we can handle events in React to interact a bit more with the DOM. For more information regarding React or to be sure not to miss an update, you can find me on twitter.